Note: All new content is published at my new website, AaronNewcomer.com. This site will remain around until everything is transfered there.

Please visit AaronNewcomer.com to see lots of new articles on pinfire guns, Pauly guns, rare gun-related journals and books, unique cartridges and more!

W. Tibbals Revolving Firearms Patent

September 24, 2019

One of the most famous American ammunition manufacturers was William Tibbals. William Tibbals was the partner in the company, Crittenden & Tibbals, who supplied mostof the rimfire ammunition during the American Civil War.

Part of what made Crittenden & Tibbals so successful was their early relationship with firearms manufacturers such as Smith & Wesson. Crittenden & Tibbals made some of the earliest rimfire cartridges for Smith & Wesson, Bacon, Spencer and others. I am sure that within their relationship with Smith & Wesson they were well aware with the issues of many people trying to circumvent or infringe on the Rollin White patent that Smith & Wesson had an exclusive license to use; especially since some of their main customers were some of the infringing companies.

The Rollin White patent was actually a fairly ridiculous pistol design that would have unlikely ever been made. However, there was one interesting feature about it that Daniel B. Wesson was interested in; the concept of a revolver with a bored-through cylinder which allowed metallic cartridges to be inserted from the back. This concept already existed with pinfire revolvers in Europe but it was the first time the concept was patented in the United States. So from 1855, through the next 17 years, anyone who wanted to make a revolver that loaded from the back had to go through Smith & Wesson.

During this time period there were a few notable designs that effectively evaded this patent such as the cupfire, teatfire and thuer cartridges. The revolvers that used these were designed to be loaded from the front of the cylinder and have a back that was not bored all the way through.

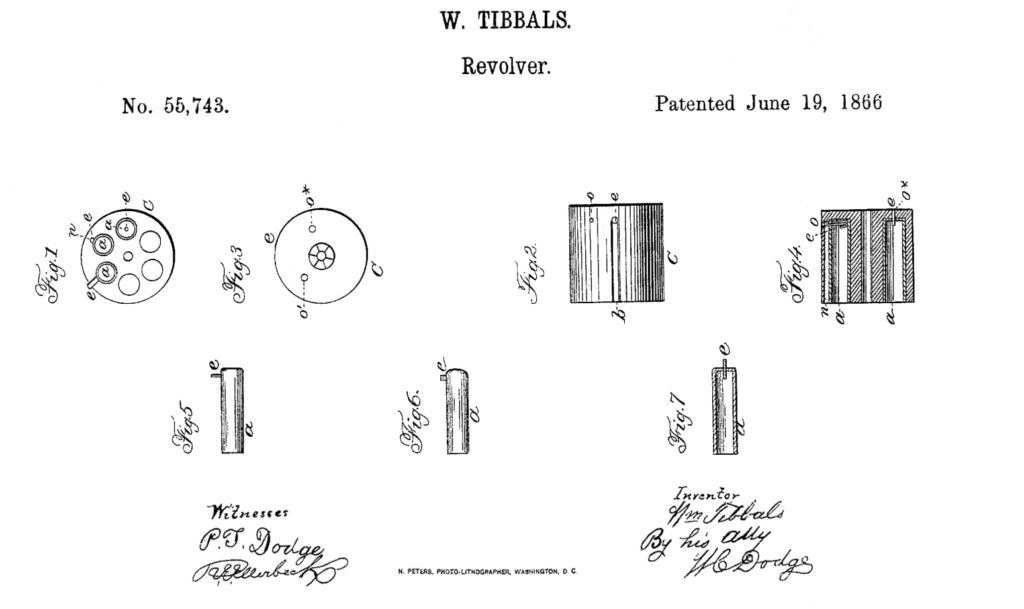

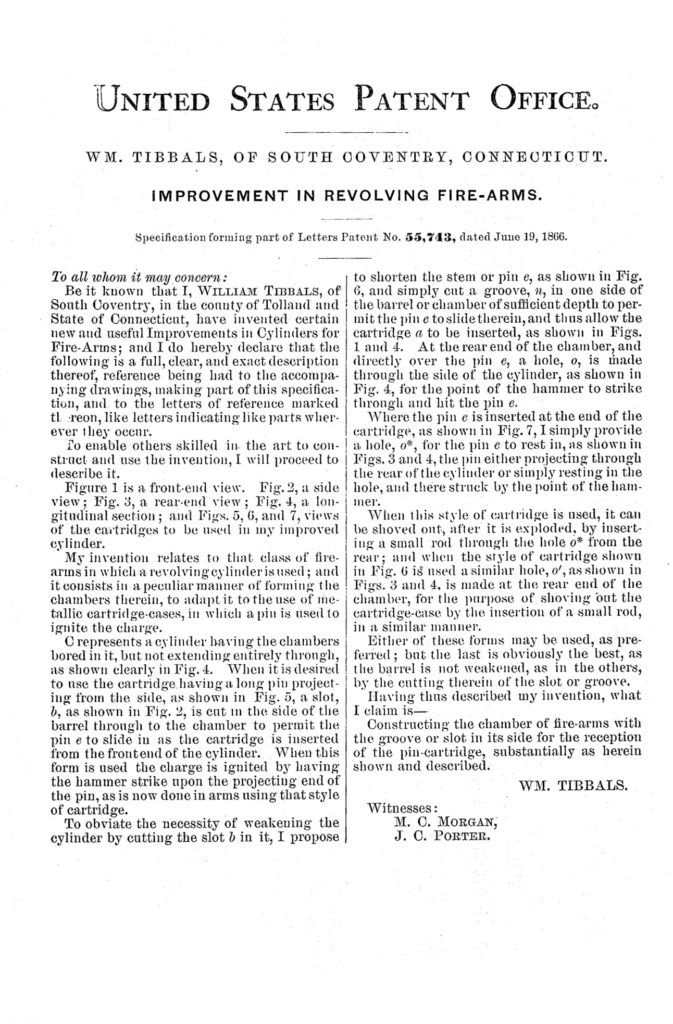

On June 19, 1866, William Tibbals was granted U.S. Patent number 55,743 for a revolving firearm improvement that evaded this Rollin White patent. His design covered 3 types of cartridges that could be loaded from the front of the cylinder; a pinfire cartridge, a horizontal pinfire cartridge and a pinfire cartridge with a much shorter pin.

His design for the pinfire cartridge put a slit through the cylinder so the cartridge could slide all the way through from the front. For the shorter pin version, he put just a grove so it would not weaken the cylinder as much.

The horizontal pinfire example would have its pin stick out the back (where the wire is in the following picture) where a centerfire style hammer would hit it. There was also a hole behind the pinfire example so a rod could push out the spent case.

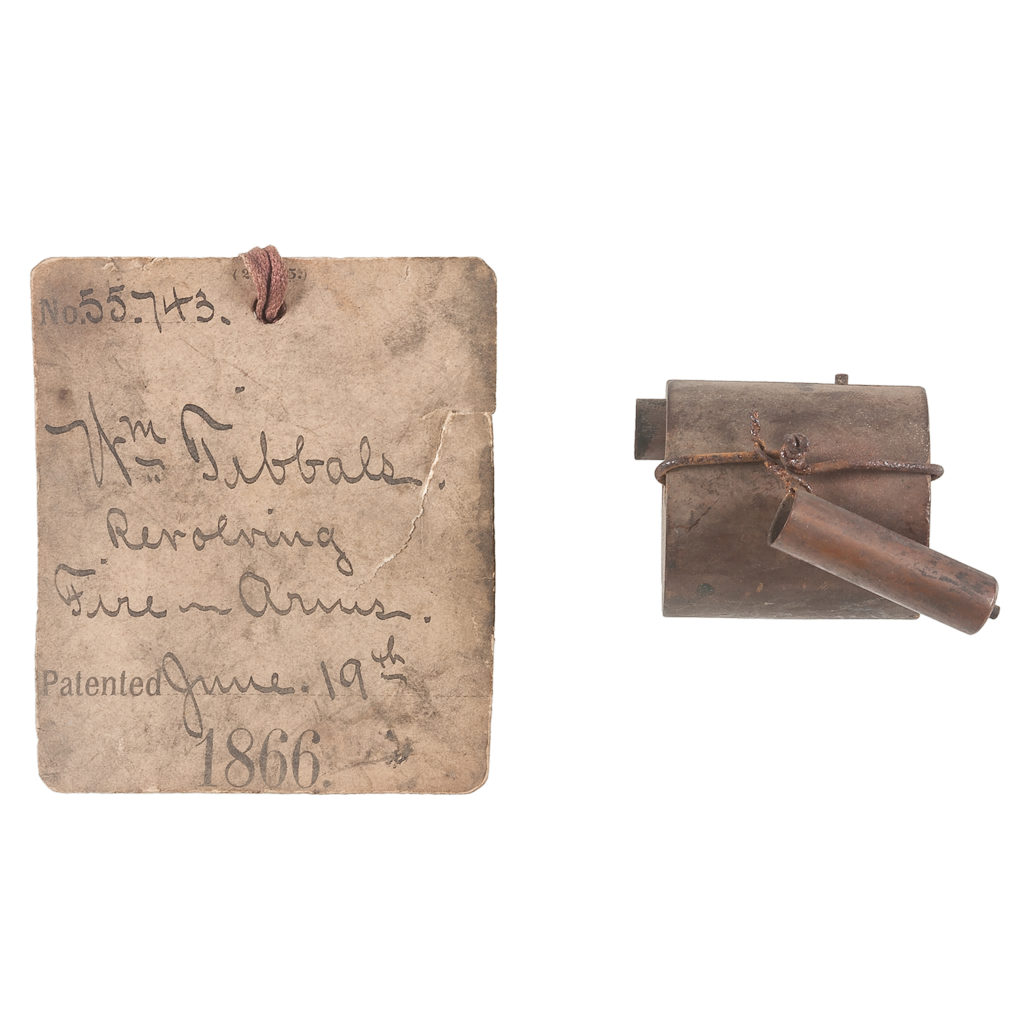

This original patent model that I acquired shows all three ways a cartridge could work with this design and has example of two of the cartridges. There are no known examples of this ever being actually made for consumers.

During this time period of ever-changing firearms and ammunition, any and every idea was worth patenting!

New Lefaucheux Pinfire Forum

August 28, 2019

I have created a new community at https://CasimirLefaucheux.com for anyone to talk about pinfire guns, pinfire cartridges and anything related to the Lefaucheux family of gunmakers.

Come join us and ask questions, share items from your collection or just learn something new! Some of the world’s foremost experts on this topic are already involved and actively participating.

No Comments »Killing Vincent: The Man, The Myth, and The Murder

March 23, 2019

This book features various images of mine as well as some original research of mine related to pinfire cartridges. I was also able to supply Dr. Arenberg with hundreds of original-period 7mm pinfire cartridges to perform modern forensic testing to determine if the autopsy of Vincent van Gogh supports the narrative that van Gogh shot himself with a pinfire revolver.

“Dr. Irv Arenberg is a retired ear surgeon, author, editor of several medical books, and an innovator with multiple patents. In 1990 he entered the art history world when the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) published his special communication that posthumously diagnosed Vincent van Gogh with Meniere’s disease, an inner ear disorder – that overturned the accepted perception that the artist had epilepsy, and more correctly explained his misdiagnosed “attacks”.

Dr. Arenberg has just finalized his most recent work, Killing Vincent: The Man, The Myth, and The Murder, a non-fiction art history expose, which sheds new light on the mysterious death of Van Gogh. Killing Vincent sets out to prove through 21st century forensic methodology that in 1890, Van Gogh did not commit suicide as is historically advocated. However, as suggested by Time Magazine, the world-renowned artist was murdered.”

No Comments »The Smallest Pinfire Cartridges

December 30, 2018This article will take a look at some of the smallest pinfire cartridges. The 2mm pinfire cartridge showed up around 1880. This is when Société Française des Munitions began producing the variations shown in the first two pictures above. These were made for tiny pinfire revolvers that looked like miniature versions of the normal pinfire revolvers.

One notable example was a revolver made in 1884 by Victor Bovy. He marketed it as the smallest revolver in the world! Scientific American wrote that even though it appeared to be a toy it was capable of doing a little bit of damage if pointed at the right area! They also noted that the bullet which was propelled by the fulminate alone could penetrate wood about 3/16 of an inch from a distance of 10 inches and would go through an ordinary pane of glass at four and a half feet away. These guns were really expensive though especially since they were mainly a novelty.

But then in 1899 an Austrian watchmaker, Franz Pfannl, patented a new design that was much less expensive and for the next 70 years manufacturers all over the world made these little 2mm pinfire cap guns. They put them on tie clips and cuff-links and watch charms. The gave them comical names such as Fly Pistol or Mouse Gun or Little Atom Pistol (along with the mushroom cloud logo). Most of these were made with the expectation that one would be firing blanks however, as shown on the bottom row of cartridges in the top picture, people often load a little piece of lead such as #9 shot in the cartridge and could often fire that.

Another style of these miniature guns were the ring guns. Shown above are two rare 4mm pinfire cartridges which were made for them. They are shown between a 2mm and a 5mm pinfire cartridge to give a good idea of the scale of these cartridges.

Collectors of these tiny 2mm pinfire cartridges will often collect the containers they came in as well. Below are the ones I have collected over the years.

No Comments »Underhammer Pinfire Pistol by Joseph-Célestin Dumonthier

This is a really early underhammer pinfire pistol made by the French gunsmith, Joseph-Célestin Dumonthier in 1849. It follows his 2 July 1849 French patent.

The whole barrel unscrews from the frame and allows you to load a single 12mm pinfire cartridge.

He would later become better known for making unique pinfire guns such sword pistols.

2 Comments »Pinfire Cartridge Variations from the White & Munhall Laboratory

December 24, 2018When it comes to pinfire cartridges, everything is a variation. Though there are thousands and thousands of variations, in this article we will focus on the 80 that came from the White & Munhall reference collection.

Henry P. White & Burton D. Munhall ran a development engineering lab that was founded in 1936. They were acknowledged as the leading private laboratory engaged in small arms and ammunition research and development.

At some point many of their cartridges were sold to collectors. For the pinfire cartridges, they were stored in little white boxes with the bullet pulled and case cut open to see the primer. In many cases they also wrote the powder and bullet weight on the top of the boxes. On the specimens that were not previously measured I weighed the bullets and have included that in the dataset.

There were 9 examples of 5mm cartridges including a blank and a shot load. All measurements for all sizes are in grains.

Type 5mm Avg Min Max StdDev Projectile – Ball 18.10 14.40 22.50 2.77 Projectile – Shot 8.00 – – – Powder – Ball 2.00 – – – Powder – Shot 2.00 – – – Powder – Blank 2.00 – – –

The 7mm specimens contained the most examples. Of

the 27 boxes, 24 were ball loads, 2 blanks and 1 shot. Eley

and Kynoch had the heaviest bullets while some of Sellier &

Bellot’s examples were the lightest. There does not seem to

be any correlation with the amount of powder and the weight

of the bullet.

Type 7mm Avg Min Max StdDev Projectile – Ball 52.32 23.80 65.10 10.07 Projectile – Shot 31.00 – – – Powder – Ball 5.27 4.00 6.40 0.69 Powder – Shot 3.00 – – – Powder – Blank 5.20 – – –

There were 19 examples of 9mm ball cartridges and 4

blanks. Only one of the blanks had measurements however.

Eley and UMC had the heaviest bullets while VFM had the

lightest.

Type 9mm Avg Min Max StdDev Projectile – Ball 98.57 78.50 123.50 15.16 Powder – Ball 7.76 6.90 8.60 0.72 Powder – Blank 5.90 – – –

The following picture details the 12mm cases. Most were cut down close to the bottom to allow one to easily see the primer. The crushed cases and ripped metal leads me to believe that gentleness was definitely not a guiding principle when compiling this collection.

There were 17 boxes of 12mm cartridges including 1

blank. The last bullet pictured below was actually not from

the collection. I included it here as it is just a neat variation

that has S 8 84 stamped underneath the bullet. I would love

to find out information about it.

One interesting piece of data is that the American-made

cartridge by C.D. Leet (top right bullet, below) only had

20.70 grains of powder. While that is nearly double any

of the others, it is not quite the 25 grains ordered by the

Frankford Arsenal during the American Civil War for these

cartridges.

Type 12mm Avg Min Max StdDev Projectile – Ball 167.97 113.60 209.80 32.61 Powder – Ball 11.43 7.20 20.70 3.94 Powder – Blank 11.50 – – –

And last up are three 15mm examples. They are all the long

case variation.

Type 15mm Avg Min Max StdDev Projectile – Ball 413.27 350.50 449.40 54.56 Powder – Ball 26.00 18.20 31.50 6.94

1 Comment »

The First Cartridge; A History of Jean Samuel Pauly and His Inventions

November 23, 2018As a pinfire (gun, cartridge, document, etc) collector I have always had an interest in telling the origin story of its invention. I recently had a post that showed some of the earliest pinfire guns and cartridges. But the story of Casimir Lefaucheux (the inventor of the pinfire system) starts a little earlier than that.

In 1766, Samuel Johannes Pauli was born in Bern, Switzerland, to Johann Pauli and Veronika Christine. His father was a carriage builder and Samuel started his career in this industry, selling his luxury carriages to wealthy clients as early as 1796.

In March of 1798, Pauly was an artillery sergeant in the Swiss army where he was inspired by the mobility of the French artillery that he designed a new type of artillery and carriage for the Swiss military which only needed a single horse and a couple men rather than the previous ones when needed a team of oxen to move.

But there was not a huge demand for his carriages so he pivoted to designing the first human-powered aircraft. It was a dolphin-shaped dirigible that many people were excited about. However, he did not get the funding needed so he decided to move to Paris in 1802. At some point around this time he also became known as Jean Samuel Pauly. While in Paris he had a balloon maker build his design and had a successful maiden voyage on 22 August 1804.

Then in 1808 Pauly partnered with François Prélat to open a firearms workshop. On September 29, 1812, Jean Samuel Pauly took out a French patent for a new gun design that allowed cartridges to be loaded at back of the barrel rather than shoved in from the front. This was the very beginning of breechloading weapons and cartridges as we know them.

The shotgun example shows a hinged design that opened upward to load the cartridge. He also showed a pistol design that had the whole barrel hinge downward to load. This design would be further developed and eventually turn into a design that’s still used to this day on shotguns.

His cartridge that worked with these designs was rather revolutionary as well. It consisted of a small metal base that was sized to where it would perfectly fit in the opening of the breech on these new guns. A paper cased cartridge would then be fitted to the front of the metal piece and tightly tied to the metal base. He also mentioned that many other case materials could be used, including metal, which is shown on my example.

Cartridges that contained the projectile and powder all in one piece had been around for awhile. Pauly took this idea and made it even better. Rather than having to have a separate ignition source such as a percussion cap that a hammer hit or a flint that struck metal like the other guns of the day had, Pauly designed this cartridge to have a slot on the base to put a priming compound that would be ignited by a spark generated from a fire piston driven by compressed air. His design mentioned that the compound could be held in place by pasting a small paper over it or a bit of wax.

The priming compound was a mixture of coal, sulfur and superoxygenated muriate of potash (potassium chlorate.) This was a delicate mixture that was hard to acquire outside of major cities.

Pauly mentioned that this design eliminates the issues that weather can cause since there is no flint or cap to get wet. It also eliminates the issues of cavalry losing what was loaded out of the barrel if the horse jerked the rider. He mentioned that this was a common thing that happened during this time. It was also much safer as there was no worry of loading too much powered in the barrel. And this allowed the shooter to have multiple cartridges all ready to go. Initial tests showed that a well-trained shooter could fire 12 shots per minute which was significantly quicker than any muzzle-loading weapon of the day. He mentions that this is 10 times faster than the ordinary guns of the day.

A contemporary review of Pauly’s gun, published 12 January 1815, in the Journal de Lyon, ou Bulletin Administratif et Politique du Département du Rhône states that the guns are much easier to use, almost never misfire, can be used in the rain by hunters and can even be safely used by children. It states they are easier to clean since the barrel is open at both ends and there is less smoke so you can actually see the animal fall after shooting it.

Another contemporary review was written even closer to the date of invention. It was reviewed by Baron Delessert, in September of 1812, in the Bulletin de la Société D’encouragement pour L’industrie Nationale, who had reviewed Prélat’s new rifle a couple years prior. He mentioned that Pauly was working with Prélat to manufacturer these guns. The article first goes into Pauly’s details of the gun on how it is faster, safer, better and all of the marketing talking points. He then goes into his personal review of the gun. Delessert shot 300 rounds through the gun and indicated that not a single shot misfired. He mentioned how this gun would be especially beneficial to cavalry since there is no worry about the charge being dislodged from the horse jerking. He also mentioned how advantageous it was that there was no smoke or bright flash from the primer ignition which allowed more accuracy on multiple shots. And just like Pauly’s claims, Delessert’s review indicated that using this gun was much faster and easier than anything that existed on the market. He also mentioned that it would likely be less expensive than other guns of the day once it was made at scale, especially since it used half the amount of powder.

Pauly tried to sell this gun to Napoleon’s army and even though it was an amazing design for the time it was still turned down due to the need for two types of powder, its cost, its complexity and the unknown of how safe it would be.

At Pauly’s Parisian factory he employed a couple men who have been mentioned before in this blog. Both Casimir Lefaucheux and Johann Nikolaus von Dreyse would get their start working for Pauly and go on to patent their own designs and become far more famous and wealthy than Pauly ever was. Then in 1814 Pauly moved to England. He sold his factory and patents to Henri Roux who continued to manufacturer an improve these guns in France.

When in England, Pauly would become known as Samuel John Pauly. He established himself on Charlotte Street and partnered with a well-known businessman, Durs Egg, to continue working on his flying machine. On 25 April 1815, the king granted a license to build a passenger air machine which would be able to transport 15-20 people back and forth to Paris each day. On 16 August 1816, the London Observer reported that the ship was almost ready to fly but the maiden voyage never happened and the exact reasons are unknown.

During this time of working with Egg, Pauly had not forgot about his revolutionary firearm design. While in England, Pauly took out two more patents for modifications to his gun. I recently acquired a copy of both of these British printed patents. The drawings are printed on a linen paper that folds out to be about 4 feet wide. I am not sure I have seen them published anywhere so I scanned them and will provide them here!

The first patent was granted on 04 August 1814 and covered a new design of using compressed air to move a fire pistol that created a spark that ignited the priming compound. The heat from this would then ignite the priming compound or powder. It also covered a cannon that used a similar ignition design.

The second patent was granted on 14 May 1816 and improved on the first. It covered the pistol and more variations of the gun. It also went into much more detail on the cannon. I do not know if this was the design he had made for the Swiss army, but improving artillery was clearly something that was still on his mind.

Henri Roux would bring these modification back to France in additions to the French patent. He would also patent a flintlock variation of the gun. In 1823 he would file a new patent to allow the Pauly design to use the more common mercury fulminate priming compounds.

In November of 1823 Henri Roux would then sell the company and patents to Eugene Pichereau who would further improve the design of the gun and especially the cartridge. His modifications to the cartridge added a nipple which allowed the priming to use a normal percussion cap so it was easier for people to use and find.

In July of 1827, Pichereau sold the patents and company to Casimir Lefaucheux who patented one final addition to the Pauly design and unsuccessfully tries one last time to sell it to the military. He then stops working on the Pauly system and begins working on his pinfire system and improved breech-loading design.

In June of 1836, Lefaucheux sells the Roux patents and his own patents to Jubé who will manufacturer Lefaucheux-style weapons for the next decade until Casimir Lefaucheux ends up buying them back after taking a long sabbatical from gun making. By this time the advantages of the pinfire cartridge, such as being more gas-tight, safer and less expensive to manufacturer set it up to become the first cartridge weapon adopted by a military in France. His legacy would continue with his son, Eugene Lefaucheux, whose pinfire weapons would be adopted in some form by nearly every military in the world and become the most popular thing in Europe for half a century.

No Comments »Eley’s Earliest Shotshell Patent

November 3, 2018Pinfire shotshells first show up in an Eley price list on 31 August 1860, It was in a trade journal called The Ironmonger & Metal Trades Advertiser. They listed 1000 12g shotshells for 50 shillings as well as 1000 16g shotshells for 40 shillings.

On 13 April 1861 William Thomas Eley took out a patent for an improvement to the pinfire shotshell. The key aspect to this patent was to better fix the cap into the case and prevent the pin from flying out of the case on detonation.

This idea would be further refined in 1869 and become one of Eley’s main advertising features; their patented gastight cartridge. These gastight cartridges had a metal inner lining that would prevent the case from expanding so much that it would separate from the base allowing gas to escape.

This feature is actually present in these 1861 patented cases. However the most notable feature is that the headstamp says 1861 on it.

The writer of the book, Eley Cartridges, believes that this is Eley’s first shotshell. He believes that the cartridges in their 1860 ad were ones they resold from a French manufacturer.

I do not believe that these two ideas have to be mutually exclusive. I think the cartridges Eley listed in 1860 could easily be the same design he patented in 1861. There are many examples of cartridges by various companies existing before they were patented. However there has never been a 16g version of this shotshell discovered.

It is also possible that there was a completely different design that existed the first year. This actually makes even more sense for specifying 1861 on the headstamp for the new ones. There is no way of knowing for sure but either way this is thought to be the earliest known shotshells made by Eley. Maybe in the future we will find something even earlier.

No Comments »The Earliest Pinfire Cartridges and Pistols

October 12, 2018This article will take a look at some of the earliest pinfire pistol cartridges. The best way to explain these will be to look at them with the guns they were designed for. The earliest examples were shotshells that were cut down and loaded with a round ball.

They were made for Casimir Lefaucheux’s first pistol design which followed his 13 Mar 1833 addendum to famous patent for the breech-loading gun design.

These were essentially just smaller versions of the shotguns he had made at the time. The rare surviving examples of these cartridges and guns seem to mainly be 24g. Other sizes such as 16g with different paper and headstamps may exist as well.

Over a decade later, on 2 May 1845, Casimir Lefaucheux patented a design for a pistol with a barrel that rotates 90 degrees to load.

He worked with Jules Joseph Chaudun to make a cartridge for it as Chaudun had recently secured a patent for an improvement to the pinfire cartridge.

Chaudun made these cartridges in ball loads, shot loads and this candle-flame bullet, pictured. The boxes that these cartridges came in actually picture the single-barrel version of this gun design on the label. The gun was made to chamber a “50 caliber” cartridge. There was also a version chambered for an “80 caliber” cartridge.

There had been some speculation over the years as to what this 50 and 80 caliber actually meant and how the measurement was made. Some people have thought it was 50 gauge and others thought it was maybe 50 lignes or points or that it was simply rounding to make it easier. But the numbers never seemed to quite add up.

I did a little more research and checked with some people familiar with old measurements and definitely think that the 50 does not refer to the old French ligne.

1 ligne is equivalent to 2.2558291mm so 50 of those would be over 112mm.

50 of the smaller unit of measurement, point, would only make it 9.4mm which is too small.

But then I began to think that this cartridge was probably first made with the round ball before the candle-flame bullet so it would make sense that 50 referred to gauge.

At the time this was made, cal 50 if referring to gauge, in Paris, would mean that you could make 50 round balls from 1 livre which in Paris (the measurements were different in different cities) was approximately 489 grammes. That would make a single ball have the mass of 9.78g.

9.78g of lead makes a sphere with a radius of 5.905mm which would make the diameter 11.81mm which is nearly exactly the diameter of these cartridges and bore of the gun.

This would make the cal 80 version have a bullet diameter of 10.097mm which matches up with guns that exist.

So I think this solves the mystery of what the 50 means on these cartridges and boxes.

A year later, on 7 Feb 1846 and on 24 May 1846, Lefaucheux had two addendums to his patent approved that covered a new pepperbox style of pistol. This gun still used these same cartridges.

Around this same time period, Gévelot also made a cartridge for these guns. It is thought that he had to wait until Chaudun’s patent expired.

Eventually the cartridge sizes became more standardized and the 12mm cartridges would no longer fit these guns.

No Comments »Extremely High Grade 16g Pinfire Shotgun by Coirier à Clermont

September 29, 2018The story of Coirier à Clermont is a interweaved tale of partnerships and encounters that begins in 1848.

In 1848 a Frenchman named Francis Marquis founded a company that made carbines for cavalry. In French this is the term, harquebusier. He was known for making high quality guns and displayed some of his work at the Exposition Universelle of 1855 in Paris, the 1862 Great London Exposition and the 1867 Paris Universal Exposition.

Shortly after the London Exposition, La Chasse Illustrée, an illustrated journal dedicated to all things hunting, featured an article about some of the high grade guns presented at the exposition. They described Marquis’s gun as “remarkable” and “a real masterpiece.”

You may be starting to wonder why we are talking about Marquis when this is an article on Coirier. Well, Marquis had an office at 4 Boulevard des Italiens in Paris. This was an office building that was used by various businessmen. There was a a steamer, a journalist, some company directors, etc. Importantly, there was also a man named Coirier, who was listed as a propriétaire. I do not know if he was the propriétaire (land/building owner) of this particular property or just one in general. But at some point he made a business transaction with Marquis. The following gun, which was sold at an auction, is marked Coirier à Clermont on the gun. The case it came in however ties this all together. It lists Coirier as the successor of the Anciennes Maison (“old house”) Marquis. Another example of a similar gun with similar markings on the gun and case was sold at a Christie’s auction in 2000.

The following invoice from 1894 makes our story even more confusing. It is an invoice by Drillien-Causin of Clermont which is listed as a seller of Lefaucheux cartridges and guns. They are listed as the successor of Labussière & Coirier.

Interestingly, there was a Coirier (partnered with a Gaguet) and a Labussière who displayed at the 1867 Paris Universal Exposition. However they were both winemakers.

Also, a Claude Jean Baptiste Coirier took out a French patent in 1865 for a cartridge crimper.

So maybe all of these partnerships and encounters all weave together to tell a single story or maybe there are just a lot of coincidences. Either way this gun that was retailed by Coirier à Clermont is one of the highest quality pinfire shotguns I have come across.

The barrel was made by award winning, Massardier-Poulat of Saint Étienne, France. Maybe the rest of the gun was as well. He won awards at the 1867 Paris exposition that everyone in this story seemed to display at.

It is proofed in Saint Étienne, France and is marked as being 34 bore. This 34 is based on the old French Pound (Livre.) It is essentially a 16g pinfire shotgun. Based on the proof marks it was made between 1856 and 1868. Based on the information we could find on the various retailers, it most likely dates closer to 1868 than 1856.

No Comments »Page: 1 2 3 4